RECLAMATION : DEADPOOL

Mark Twain may have said, "Whiskey is for drinking, and water for fighting over." But, during a presentation to 1893 irrigation conference John Wesley Powell said it more clearly. “You are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” The Colorado River has been the center of that struggle for over 100 years. To coincide with the 100th anniversary of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, my ongoing multi-part project, Reclamation, examines the history and future of the Colorado River and settlement in the Southwest.

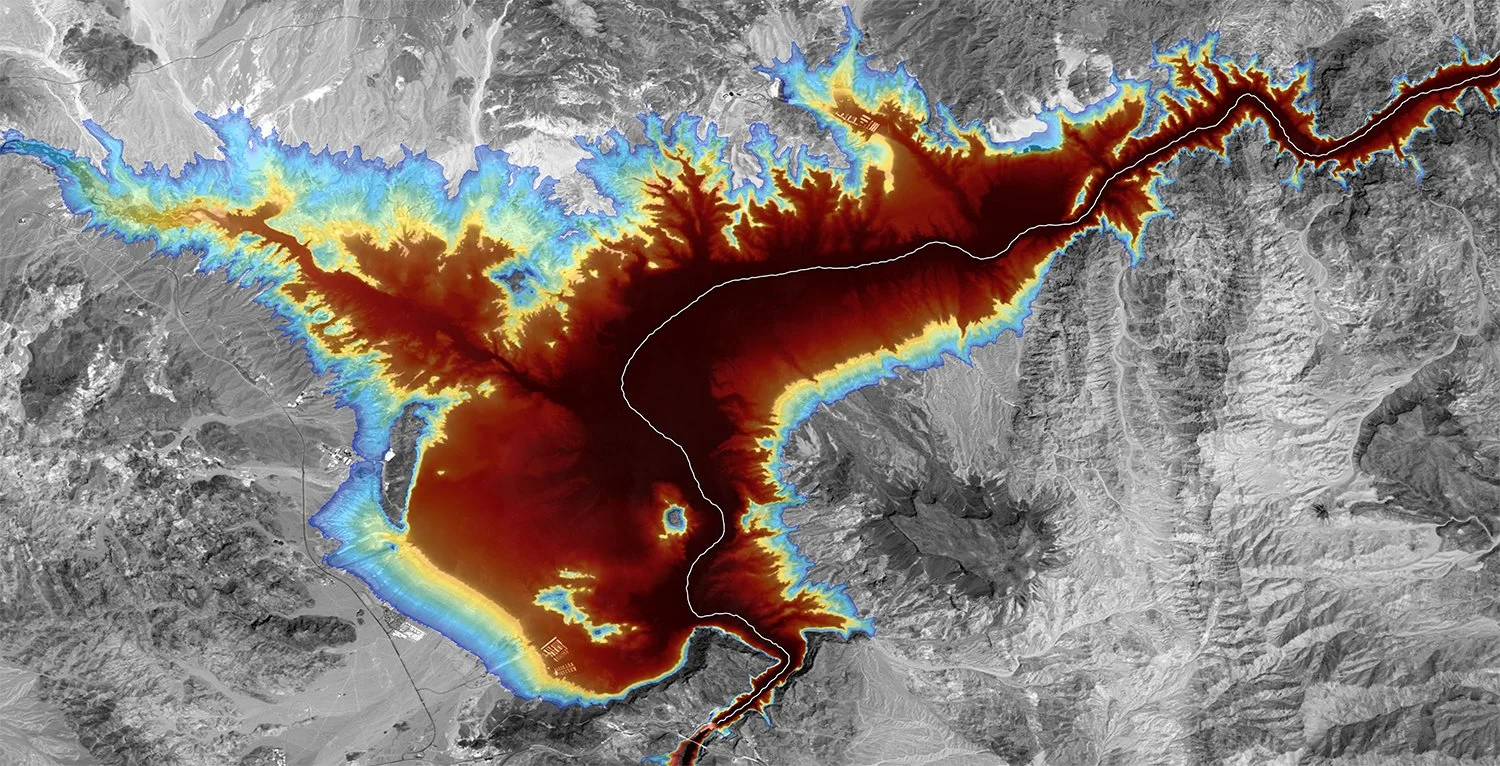

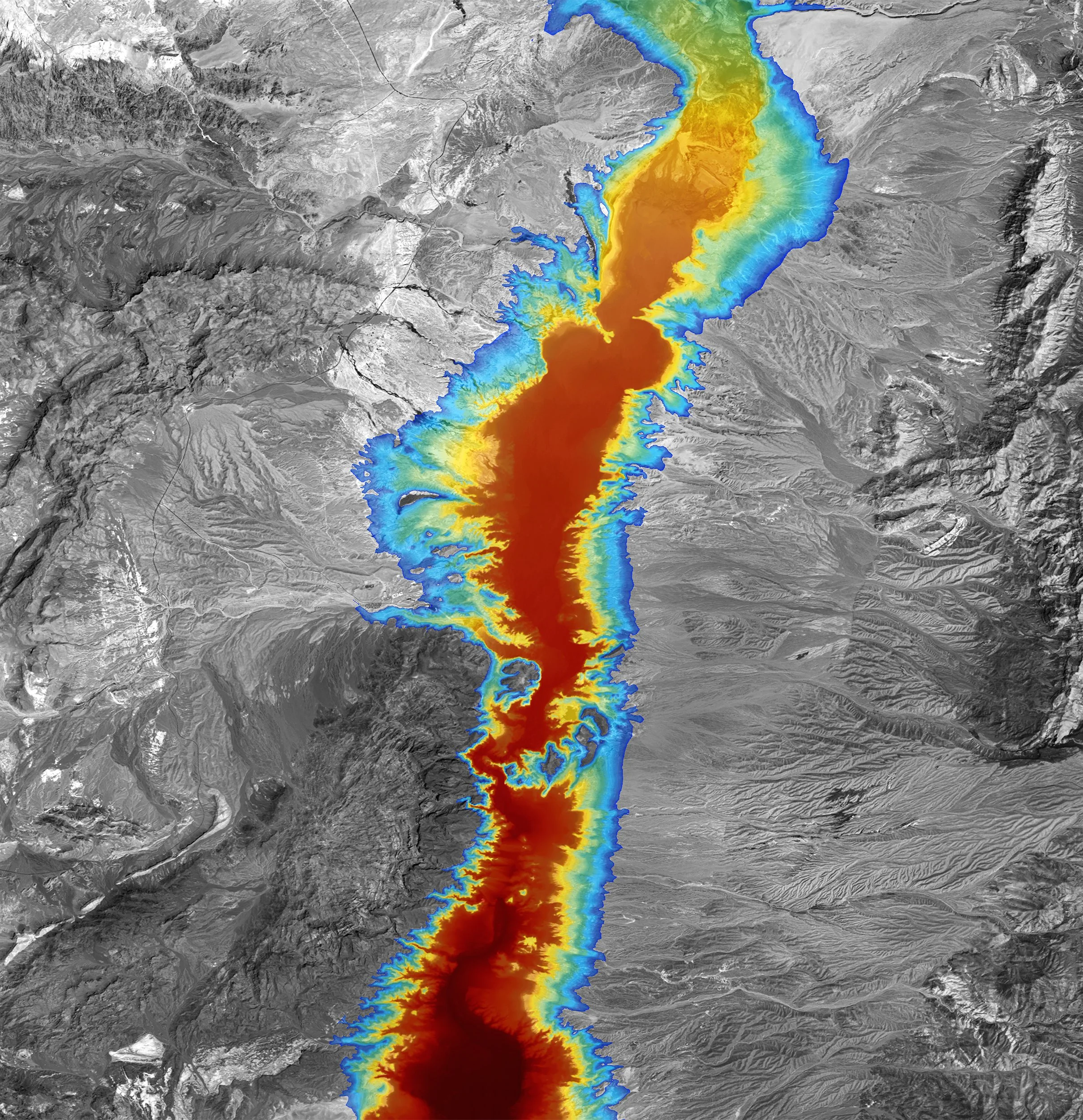

Deadpool focuses on the nation's largest reservoir, Lakes Mead, and uses the bathtub ring, the 160'-180' tall white mineral deposit left by the declining lake elevation, as a symbol for the inescapable reality of the accelerating impacts of climate change. Along with my photographs, I use geographical information software to create custom maps from remote sensing imagery and elevation data.

Underling this project are Powell's recommendations for how to structure the settlement in the arid regions and late 19th and early 20th-century politicians' willingness to ignore science and the reality of how much water the Colorado River could supply. The project links the long history and almost supernatural draw of the Southwest, how 20th-century reclamation projects made living there possible, and how climate change now threatens the future of the 40 million people dependent on the Colorado river for water and power.

The speed at which the water levels have been dropping at the Nation’s largest two reservoirs—both on the over-allocated Colorado River—have made me think about a kind of picture that could be a symbol of the water crisis facing 40 million people in the Southwest.

Now, both Lakes Mead and Powell are roughly 1/3 of their capacity due to a 20-year-long “mega-drought” and the impacts of climate change—the most dramatic losses within the last year alone. Their walls are stained with the distinctive white bathtub ring formed by mineral deposits from when the lakes were last considered full. In some places, it reaches as high as 160 feet above the current water levels—lowest since being initially filled. While the the low water levels from the past 10-15 years signal danger for the people living in the West, it also means that, at Lake Powell, some of that beauty that was initially lost is starting to come back.

The shrinking lake levels are made worse by the ever-increasing consumption of the water from the Colorado River, the warming and further aridification of the West, and the accelerated loss of water due evaporation, seepage, and lack of snow in the Rockies and other ranges feeding the tributaries of the Colorado River.

By focusing on photographing Lake Powell and Lake Mead—the United States’ two largest reservoirs and greatest symbols of its reclamation projects—I aim to illustrate the historical conflict and balance between environmental conservation, recreation, and the realities of supporting sprawling cities and agriculture in places with so little water.

I hope the project also brings to light how John Wesley Powell's recommendations for responsible settlement of the West were ignored in the interest of politicians and speculators. Powell, the namesake of lake, was the leader of the first recorded expedition on the Colorado River through the unmapped areas of Utah and Arizona, and who later became the 2nd Director of the US Geological Survey. While his expedition down the Colorado River gets the most attention, his 1875 Report on the Arid Region of the United States is too-often overlooked. In it, he argued there was not enough water in the Southwest for the widespread agriculture and settlement that eventually take place. His report and recommendations to Congress were ignored and western settlers were promised that "rain will follow the plow." Those early homesteaders were lied to, and unprepared for a landscape that couldn't support an Eastern agricultural model and soon faced the consequences of politicians not listening to the scientists of their time—something we are still dealing with in the face of climate crisis now.

“Since 2002, the National Park Service has invested tens of millions of dollars to extend launch ramps, parking facilities, water systems, electrical systems, docking facilities, navigational aids, shoreline access, sanitation facilities, and many other facilities to accommodate lowering lake levels. The park continues to work with BOR and other partners to develop a range of options to address changing lake levels.” — National Park Service

Lake Mead, when near capacity, reached up into the western-most portion of the Grand Canyon, where the Colorado River punched through the the 1000-foot wall of the Grand Wash Cliffs and Iceberg Canyon. Now the river, and the millions of tons of silt an sediment it can no longer carry, extends to Sandy Point and South Cove. Grand Canyon River trips were able to exit the river at South Cove. As drought conditions worsened over the last 10-15 a new un-navigable rapid formed one mile further down river the from the original Pearce Ferry take-out point. This require the Park Service to spend a million dollars to extend Pearce Ferry Road to the now free flowing river.

2021-2022 book now available

Photographs, text, and maps by Richard Boutwell

Variation 1, Printed in an edition of 50

6.2 x 9.7 inches

Softbound, 28 pages, 36 reproductions

Deadpool is small book from work made on and around Lake Mead between September 2021 and January 2022 as part of my ongoing series photographing the 20+ year mega-drought and Colorado River water crisis.

Sales from this book go directly back to funding more work on the project.